So when I received an email saying that Oxford’s Story Museum would be holding an event in just a few weeks with the incredible Michael Rosen and none other than Professor Jack Zipes, I flailed. Shouted for Mum (who first introduced me to fairytales after all). Flapped a bit. And excitedly booked my ticket. The queue, when I arrived on Friday 29th April, was stretched around the street.

The Story Museum are running a series of events called ‘1001 Stories’, a Scheherezade (which I just spelled correctly on my first attempt, go me!) experience with experts from around the world.

‘The Story Museum exists to celebrate children's stories and to share enjoyable ways for young people to learn through stories as they grow.’ I love this mission statement. However perhaps this particular talk should have come with a warning label for little children, as one little girl and her mother hurriedly scurried away upon realising that the true tales of the Brothers Grimm are not quite the tales from Orchard or Usborne.

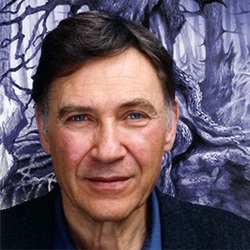

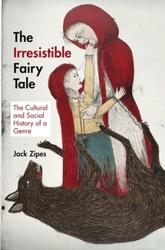

Jack Zipes is a published author, translator of Grimms fairy tales, Professor at the University of Minnesota, and a story teller in an array of state schools. He believes that fairy tales weave narratives into daily existence, bound into cultural traditions that deal with basic human problems. They are basic stories that deal with every day existence and they are necessary because life is hard.

Fairy tales, says Zipes, give us hope that we can resolve conflict.

Mr Rosen led a lively discussion exploring Mr Zipes' expert opinion on all things Grimm.

These tales aren’t the animated glitz of Walt Disney. Red Riding Hood, as many are aware, is about the rape of a young girl. Emanating from patriarchal traditions, the girl is shown to have brought the rape upon herself by not adhering to the rules. According to Zipes, many story tellers try to pretty it up. In the Perrault version she is gobbled up. The message seems to be that little girls who invite wolves into their parlours deserve what they get. Great storytellers change this narrative to reflect a different perspective, what Zipes calls the anti-red riding hood. It is his belief that publishers stupidly publish tales that put the onus on the little girl. Angela Carter’s The Company of Wolves gives tales such as these a feminist spin and reclaims them without sugar coating.

The talk turned to recent television shows from the US such as Once Upon A Time and Grimm that Zipes believes lazily recreate the tales without artistic vision. He believes that writers should take the Grimm brothers seriously and explore all the tales, not just the famous and familiar. We asked Mr. Zipes why he believed retellings such as these were so popular now? He responded that magical narratives involve spectacle, and digital film making lends to magic. Even, he grinned, with awful films like Witch Hunters. He also noted that with films and shows like these the evil is in the hands of a woman, and that Hollywood is involved in a strange backlash against feminism that has been occuring from 1980s to today. Furthermore he says that with the recession and suffering in society, fairy tale films with saccharine plots or needless special effects are diverting. He worries that shows and movies such as Mirror, Mirror dumb down the tales until they no longer reflect their true purpose. Authors and publishers should aim to produce artful tales that Western cinema overlooks. This discussion is explored more thoroughly in Mr. Zipes book Enchanted Screens.

My sister and I are watching Once Upon A Time, and whilst I agree that some plots are replicated and mishandled, that stereotypes prevail, I do think that the narrative is handled with more care and intricacy than some of its comparisons here.

Zipes is currently working to translate the original collection of Grimms tales, first published between 1812-1815. There were seven different original editions compiled by the brothers. The last editon was published in 1857. The most well known version was published between 1826-58, a smaller collection of just fifty tales.

In Zipes' opinion, the 1812 edition is the closest to oral tradition. These were brutal honest reflections of rural life, for example How Children Play with Slaughtering in which young friends decide to play act a butchery. ‘I'll be the pig, you be the butcher, and the girl collects blood in pot.’ The ‘pig’ is offered a choice, apple or knife, and the tale ends in an execution. Many of these tales explored death. Another featured brothers again play acting butchery whilst a mother watches on from a window. Appalled she leaves behind her baby, who dies whilst she punishes her son. Torn apart by grief, she commits suicide. These huge themes of family loss told in a blunt unique style are certainly not magical. They maintain German Nordic tradition, which includes very few fairies. The moral to the story is that two older brothers WILL try to kill you.

The erudite brothers were writing in their early twenties. Wilhelm Grimm (the younger brother) acted as editor between the editions, adding in Christian elements and in tales like Hansel and Gretal going so far as to change family connections to create a more nuclear bourgeois setting. The book became more literary, with changed style and key motifs. Zipes believes that Wilhelm was doing what good storytellers do, and embellishing. However it caused much debate between the brothers, with Jacob the elder preferring the printed originals of the first edition. Wilhelm wanted it to appeal to masses.

The first two volumes were not intended for children. They included no drawings and looked like the rough first edition. They didn't sell well. Jacob allowed Wilhelm to make changes within the tales after receiving criticism. And the Grimm policy to keep strictly to the oral tales in written form changed in 1823 after receiving Edgar Taylor's popular stories. These were illustrated by George Cruikshank, had a sense of humour and were sold as a book for children. It did so well that it got two editions more printed in same year. So Grimm did the same, picking hopeful tales in a smaller volume for children, which his brother Ludwig illustrated.

In England this translation was the only one available until the 1850s. The English had no idea what the full book was like in the 19th century. Most English households are still unaware of what the ‘real’ tales are like, familiar with the many rewrites and censored editions. Puffin have published three different editions of Grimm for children, a hardback and two smaller paperbacks, but using Taylor's tales, not Grimms! They are able to make profit from Cruikshank’s illustrations and stories that are in the public domain.

Zipes' theory is that the brothers felt by this point that they knew oral tradition, and understood the essence of storytelling. Therefore above all else they wanted the tales to resonate with readers. They also wanted to leave their own legacy.

In some examples of changes made, the Snow White of the 1812 edition was originally more like Carter's Snow Child in The Bloody Chamber, the girl abandoned by her father and jealous mother on side of road. In another edition ‘Mirror’ was the name of a dog, with the queen calling ‘mirror mirror!’, and the dog speaks back. There was no major role for the prince in these tales, they were not romance. The Grimms purposefully changed the status of the mother from biological to a step mother, for the sanctity of their Christian beliefs regarding the Holy Mother.

When asked for recommendations for fairy tales with strong female characters that did not resort to masculinisation of females in order to make them appear less 'weak', Zipes suggested Angela Carter’s anthology. But he also noted that some of the original tales from the Grimm brothers were supportive of strong women, for example the tale of the clever farmer’s daughter. Clare Keegan’s Irish stories offer folk examples where women control the choosing of their husbands.

During the question and answer session at the end of the talk, Mr Rosen opened up the discussion to the floor. My teacher at Oxford Brookes, Sally Hughes, asked how the books were received by readers at the time. Zipes explained that it was not until 1840-50s that the tales took off. Hans Christian Andersen was much more popular. But the Grimm brothers became part of the school curriculum in the 1870s, when the German nation united. Bourgeois families recognised that the original tales were not quite child friendly, but once accepted by the schools the smaller edition leaked back into family homes. Single tales also appeared in ‘chap’ books. These short narratives were chunkable, and publishers could take advantage of publishing one at a time. To aid in this practice, Wilhelm added proverbs and changed phrasing adding greater historical depth such as passages from the Luther bible.

The Story Museum is part of the Happy Museum project, hoping to build an arc of stories, from all times and places. As well as their dramatised 1001 stories series, they ask visitors to leave behind a book recommendation on paper stars to add to their collection of narratives. I chose Malindo Lo’s young adult retelling of Cinderella, Ash, to add to archive as I think Mr. Zipes would approve of the critical thinking and narrative intent behind the story.

The next event run by Story Museum is with author Kevin Crossley-Holland on 10th July discussing Norse Mythology.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed